You must forgive my gushing about Buster Keaton. I do understand that this is not (technically) related to British television. But as I've said, the beauty of having your own blog is getting to write about whatever you want. ... And what

I want right now is Buster Keaton. If you don't like that, I suggest you get your own blog ; - )

My discovering Keaton is like discovering Cary Grant. I did the latter in my teens. How on earth did I get this far in life without knowing the incredible talents of the former!? His work is

profoundly good and I feel compelled to spread the word. Any fan of quality film and tv, which you obviously are, should make a point of seeing his work. (Go on; go do that now. Try Youtube. I'll wait. On second thought, you'd best read the post first.)

To those who might not realize this, Keaton was not just a slapstick comedian of the silent age. He was a talented director who conceived and filmed original ideas in movies that are tight, well acted, beautifully photographed, subtle, and touching. Oh, yeah, they were funny too. They present such well-made stories, that even modern audiences raised on a barrage of color, sound, and special-effects will be won over. My younger son asked me a couple of days after watching

The General, "mom, did that movie have sound; I can't remember?" A telling complement.

The General is so exciting and so very watchable you don't even

notice that it lacks dialog. Keaton's films are like that. Treasures for all time.

The four feature films that follow are my personal favorites and those I consider his best work. They are quite distinct in their characters, plots, pacing and style. Yet they all bear the unmistakable stamp of Keaton. That "stamp," as I see it, is to make reality feel good. His films are rooted in real truths about the simplicity of plugging away through life, meeting challenges that arise, fighting, moving along. And accepting it all with eyes wide open and lots of humor. His world is not perfect by a long shot, but its never depressing -- because, he (through his wonderful characters) lives life so well. He is beautiful in the fullest sense of the world. And he makes me want to live my own life with more precision and grace - he makes me want to jump on things, bend backward, go do something! Buster inspires me and somehow makes me feel as if I could.

The General.

Few will argue with this selection. It's the equivalent of saying that

Imagine is John Lennon's best song.

The General places on countless lists of 'the best movies of all time' and was one of the first films to be selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. Sadly, it did not garner such praise when released in 1926. Buster may have simply been ahead of his time, his adoring public appreciating him more in flat-out comedic roles, simpler of plot and less developed in theme. This movie is so much more than that.

Heralded as the next best depiction of the Civil War ever recorded second only to Matthew Brady's photographs,

The General watches like a documentary, a comedy and an action adventure film rolled together. Layered over exciting scenes of Buster chasing down enemy soldiers who have stolen his engine (the 'General'), are a sweet story of love (for his girl and for the train) and a simple story of a man who rises to the occasion that duty calls for him.

Because the film was made so very long ago -- blurring our own sense of proper timeframe -- it is easy for the modern viewer to feel as if watching something authentic to its setting. That's remarkable. Especially given that it was not even done in the South, but in Oregon, which, by the way, provides stunning scenery even in black and white.

Against this gorgeous backdrop, Keaton spends most of the movie running... around, in, under and atop two civil war era steam trains. The trains are so enlivened by his clear love and attention that they become movie characters themselves. But the best character is of course Keaton's -- Johnny Grey, who spends the movie alternating between doing things that show incredible strength and skill, with things that feel pitiful. He walks a balance figuratively and literally that is astonishing. In one striking example, the renegades have thrown a long heavy wooden railroad tie onto the track to derail their pursuer. Keaton runs ahead of his train in an attempt to dislodge the tie. He manages to do so at the last moment, tugging it free and falling into the cow sweep. With barely a moment to rest, he then sees another tie lodged halfway across the track just ahead. With precision that astounds, he heaves the first down onto the other hitting it like a see saw whereupon the whole thing springs to life and off the tracks -- not without nearly smacking him dead in the face first. The modern viewer has to know that shots such as this cannot have been 'faked' the way we are used to. Real logs. Real movie star. Real train. Moving. Real precision. Yet our hero conveys as much

awkwardness as skill in having done it! takes it in stride and climbs back into the engine to stoke the fire before the next disaster. You can't help but love this man.

The stunts come fast and furious (including one so stunning it still shocks: the sight of the steam train "Texas" collapsing a burning bridge and plunging into the river below). Underlying the whole is a movie with so much heart that it makes yours ache. In one such scene, our hero has rescued his girl from the bandits and they are hiding out in the woods in the rain. Buster is kneeling on the wet ground next to her when she lays her head upon his chest and tells him he's brave. He puffs with pride and he cradles her to his breast with the look of utmost pleasure. You can feel his heart swell. Light fades and when morning dawns, it dawns on him sitting just there, having held that position all night - clearly unwilling to lose the moment. Only the subtlest attention is drawn to this, by him stretching out those bent legs in the morning.

Buster Keaton's uncanny way of underplaying a moment is his greatest charm. Like his choice to follow that tender declaration with a scene where he stuffs his love into a gunny sack to smuggle her out of enemy camp, and then steps on the sack several times before freeing her. Marion Mack, the actress who plays his love gives a great comic performance. She is game for this treatment and more and really gets to shine in the last half of the movie as she helps foil the bad guys, behave heroically and take her own pratfalls such as getting hilariously doused at a water spout.

The film hits it on all fours - everything a movie should be is wrapped up in one very beautiful package. It should be on any movie lovers 'must see' list.

Sherlock Jr.

The General may be the critical consensus for best, but my favorite Keaton movie is

Sherlock Jr. (1924). Profoundly interesting and well made,

Sherlock Jr. is simply unique. When you have a lot of experience watching movies (!) and are plumbing the depths of 90 year-old work, you just don't really expect that many surprises. But

Sherlock Jr. surprises. It actually astounds.

Our hero is known simply as 'the Boy.' He's unskilled but confident. He works as a projectionist but dreams of being a detective. Keaton gives a great nuanced performance -- imbuing the Boy with dreams and longing, shyness, the desire to step up and be a man, and an overarching fear of failure. He's so timid with his girl that he can't look at her when he gives her a ring. But, he fearlessly tracks his suspect all around town when framed by his rival for the theft of a watch. In this production Keaton wears many hats very well (figuratively in this case.) In addition to the great acting he brings, Keaton the comedian is there, hilariously walking in lockstep with the suspect and performing clever vaudeville stunts. Keaton the director brings pacing, location, style and visual appeal. There are wonderful sweet details to the movie like having "the girl", played by Kathryn McGuire, actually solve the crime herself in a matter of minutes while Buster is out bumbling around. (I'm not going to climb too far out on a limb and claim him as an early feminist, but I do notice that in many of his films, the leading ladies are doing resourceful, intelligent and

active things rather than sitting around waiting to be rescued. This makes me love him more.)

All these details come together to cause the film to feel complete and engaging, but the real punch is packed by its technological wonders. When the Boy gets back to his projector and starts the afternoon's show, he dozes off. Several amazing things start to happen. A hazy second-self wakes up, fractions off from the Boy, and walks away. He steps through the audience and orchestra and into the playing movie, with in-camera effects that are so well done that they look beautiful, convincing and evocative even in 2012.

What makes these scenes remarkable is not that Buster Keaton was able to achieve them, technically speaking, but that he was able to weave them, artfully, into a story where they actually matter.

Sherlock Jr. is the antithesis of the early sound movies that used sound just to show that they could. These effects are central to the themes of reality, fantasy, dream and hero. When the Boy enters the picture and attempts to interact, he is expelled from the action. Another astonishing editing sequence shows Buster as the Boy in (quasi-)stationary position as the scenery in the movie continues to shift around him -- the background becoming a garden, a rocky outcrop, a jungle, a desert and a snow bank, etc. The effort involved in piecing together this nearly seamless sequence was massive. And it's beautiful work. But what makes it mind-blowing is that it is used to further the story. The viewer learns that the Boy doesn't belong in the movie, which moves mercilessly around him; he's not part of it.

Not until he finds a role he can dream himself into, can Buster enter the movie. So when the bad guys on screen concoct their nefarious plot, Buster's sleeping Boy enters the action as the "crime crushing criminologist Sherlock Jr." . . . As smooth, suave, Sherlock Jr., classy, well dressed, and smart, Buster gets to play an extremely attractive leading man. Its a delight to see.

At this point in the movie the technological thrills give way to ones that come from Buster's physical brilliance, starting with Sherlock shooting a deadly game of pool with stunning accuracy and managing to miss the ball that's been rigged with explosives. Or, my favorite, Buster riding on the handlebars of a motorcycle after the driver has been kicked off. Cars, puddles and men with shovels can't unseat him as he speeds along through the streets of LA and deftly past the still undeveloped hills of Southern California. While on the handlebars, he crosses a gaping bridge by riding across the tops of two trucks moving in opposite directions -- meeting up with them at the very moment that they align creating an insanely dangerous and transient bridge. Its impossible to overstate how well-orchestrated that stunt had to have been! [

See my note in the comments below on this stunt]. I've noted before that these scenes play like James Bond (40 years ahead of schedule), so I was thrilled to hear, on the dvd version of the film I recently watched, that Bondesque music was playing in the background. Apparently I'm not the only one making that association.

The movie, at just 44 minutes, is a fast and furious ride. A great comic ending follows the joy ride when our hero reintegrates himself, reencounters his real-life lovely, and re-proposes -- taking his cues from the lead actor in the movie that is still chugging along on screen. Its a wonderful way to wrap the experience.

Steamboat Bill Jr.

This movie is the height, the absolute apex of charm. Pitting rough, river-rat dad and his dandy of a son whom he has not seen for years, Keaton has chosen a theme that has been subsequently and continually worked for laughs by many over the decades. Buster's endeavor in 1928 may not have been the first to attempt it, I don't know, but it certainly has to be one of the best.

Gruff dad, played beautifully by Ernest Torrence, does not do the best job masking his disappointment in how his son has turned out, but he tries to make the relationship work. That is, if by 'make it work' you mean 'force Bill Jr. into being a more suitable son.' Buster was put on this earth to play the role of Bill Canfield Jr.. He is perfection as the foppishly cute, childishly stubborn, but basically moldable son. He follows dutifully as dad pulls him along by the hand. He gamely lets dad call the shots on mustache- and ukulele- removal, as well as clothing and hair readjustment, but when he runs into his college girl friend (who unfortunately happens to be his dad's arch-rival's daughter), he draws the line. Buster's not giving up King's daughter (played deliciously by Marion Byron) and who can blame him; She is the cutest, spunkiest, gamest costar for Buster that I've ever seen. Her talents suit his extremely well and their scenes together are a joy.

The father/son pairing is extremely well done and forms the heart of the movie. The scene that has stolen my heart and that I cannot seem to watch enough times on Youtube, is one where dad takes Buster to get a new hat. Buster immediately finds one he likes and tries it on for dad's approval. I love the way he thrusts his foot out and stands like a model displaying it. Dad casts it away instantly. Watch how Buster sneaks the hat back on for a try two more times (with no luck). Also watch how he secrets away his own hat into a back pocket when no one's looking. Buster's expressions while dad and the store clerk plunk a wide array of hats upon his head are priceless, but best of all is when the clerk tries a hat of Buster's Keaton's signature "porkpie" look and produces a priceless look of horror. Delightful and utterly self-aware. I love Buster Keaton.

Complications due to dad's underlying feud, disappointment with his son, and eventual jailing keep the plot humming along until the final 10 minute sequence which includes the most jaw-dropping barrage of nonstop stunts I've ever seen. No expense could have been spared during scenes of the town's destruction in a fierce tornado-like storm. The insanity culminates in the stunning scene where Keaton allows a house front to fall on top of him, just gliding over him by the slimmest of margins before crashing hard into the ground. From all accounts, this was entirely real -- with a several ton house front and a upper story window designed to give just inches of clearance around our main man. Buster could easily have been killed had anything gone awry.

Yet. . . you feel

safe watching Buster Keaton because his clear skill and precision allow you to know that he

knew exactly what he was doing. Though he does death-defying stunts all the time, they don't feel scary or reckless because of his comedic touch and because of the trust the viewer develops for Buster. His physical skill just simply can't be praised enough. The man was a genius. The movie is a smile-fest throughout. Funny, sweet, physical and charming. Another perfect endeavor.

Go West

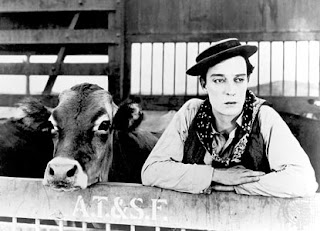

A love story about a man and a cow. That alone makes it one of the coolest movies ever.

Go West is not routinely included as one of his best, but it is. Here he matches the slower pace and tone of the movie to the work of a ranch and the heat of the desert. The scenery and buildings are beautiful and we get to soak it all up at an appropriate pace. I don't want to overstate the point that maybe you have to love the desert to love this picture, but I think it helps. You gotta be able to see the beauty of the wood in the fence boards, the dusty wind, and the windows framing the shots of the hot grey mountains. Leave it to Buster to find both beauty and humor in this landscape.

Buster's character, "Friendless," is brave in unexpected ways. First, he installs himself on the ranch as a hand with no skills to recommend him and no real contributions to make. But he shows up for supper (though it isn't until his third attempt that he gets any food) and goes through the motions. He confronts a man who is cheating at poker and doesn't back down. He is plucky and willing and has the silliest little hand gun that belongs properly in a woman's purse. Getting tired of fishing it out of the depths of his holster when he needs it, he gets smart and attaches it to a watch chain.

I always have thought that you can tell a lot about a person by the way animals and children respond to them. Here we get to see Buster's soul through the eyes of an adoring cow. "Brown Eyes" is beautiful and her clear desire to be near Buster is evident. You have to trust the cow, given that she cannot have cared about the movie biz. ;) (Another movie demonstrating Buster's winning ways with animals is

The Camerman where the most amazing relationship develops between him and a little monkey. You can't fake that.)

Anyhow, there's a scene in

Go West where Keaton is hiding behind a building watching the rancher approach his cow. As Buster crouches there, a slight wind picks up and kicks his hat off. He reaches out a hand and grabs it as it starts to blow away. He pops it back on his head almost without seeming to notice it has been blown. That in a nutshell is what's beautiful about Buster Keaton. The scene is small and serves almost no purpose. But these are the kinds of details you get with a Keaton movie. There are literally dozens of small perfect details packed into every film. This one is special to me not just because its a small detail that shows his care and attention to the way his films came together, but because it symbolizes

him in a nutshell. Its shows physical brilliance (lightning quick reflexes) and total unflappability. Life is going on in front of you and around you. Odd things happen. You just keep going. Don't worry about why. Though Buster is uber-present in the world, no one - least of all himself - sees his strength, balance, reflexes, and agility. His enormous eyes are always looking at the world with detached wonderment and interest. And together those eyes and his physical engagement make his trajectory through life fascinating, humorous and ultimately successful (in the broadest, non-sentimental way of living a well-lived life as being the only reason to wake up).

But its only the audience who really sees.

His real genius seems to have escaped his contemporary audience. They loved his humor and made him a star, but his very best and most profound work was panned upon release. Buster was making his movies toward a deeper standard -- his own. I am incredibly grateful that he got to do it as long as he could and that I managed to stumble upon it.